While you were sleeping, Part II

While you were sleeping, Part II

According to Jung, even though the “ego is the center of the personality” and the focal point of the psyche, it is still a complex (Jung et al., 1989). While the ego may inform identity, it remains beholden to our complexes (Jung et al., 1989). How often does one say or do something and even in the moment cannot believe it has been said or done? Jung wrote, “we make slips of the tongue and slips in writing and unconsciously do things that betray our most closely guarded secrets” (Jung et al., 1976, p. 28). Like the strings of a marionette, the unconscious mediates speech and behavior (Jung et al., 1973, pp. 306-307). “In the process of individuation, one of the initial tasks is to differentiate the ego from the complexes in the personal unconscious, particularly the persona and the shadow. A strong ego can relate objectively to these and other contents of the unconscious without identifying with them” (Sharp, 1991). In other words, it is possible to cultivate the ability to recognize and experience emotions without being overcome by them.

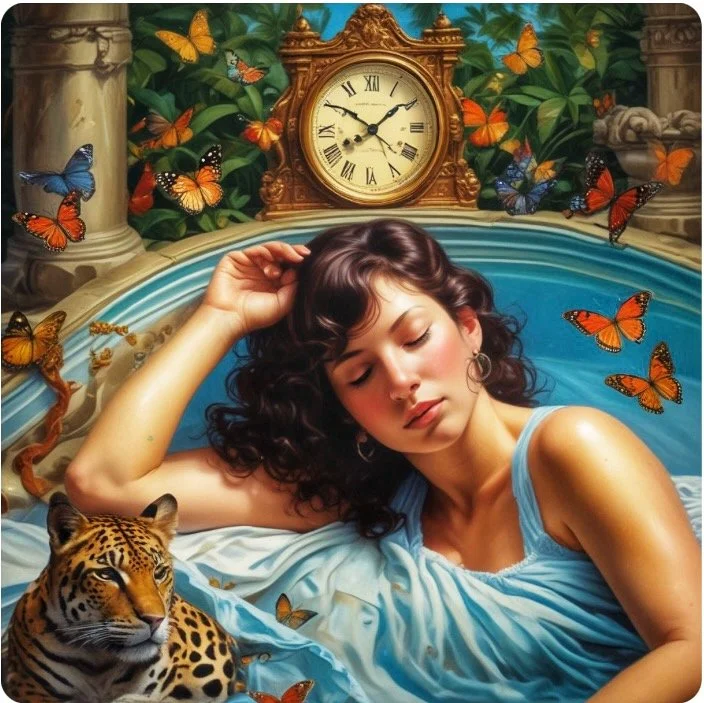

Far down the road, a black silhouette resembling a panther and her two cubs emerges from the right side of the road and crosses at a distance in front of the van. The cubs fade from view. In a split second, the large cat bounds toward the left side of the van. The panther emerges from the masculine side of the road, denoting that this message is likely arising from the dreamer’s animus. Cecilia panics, and the dreamer screams, “Make sure the window is up!”

The window delineates the separation between the personal unconscious and consciousness; the “gatekeeper” ego is attempting to moderate the emergence of unconscious content. But while the ego resists this ferocious new emergence, conscious resistance is quieted in sleep (Jung et al., 1963).

The huge cat bares its large fangs and ferociously growls. It is as tall as the window and identifiable as a jaguar.

The dreamer is assured that the unconscious material will not penetrate the window. The jaguar runs away, and they drive on.

Animals are powerful archetypal images to which humans have anthropomorphically ascribed unique attributes, such as the “wisdom of an owl,” the “pride of a lion,” or the “blindness of a bat.” Jung instructed that “it’s necessary to know the functional meaning of a symbol” (TPJ, pp. 68-69) and then discern how the contextual meaning applies. Dream symbols are a common means of discernment. When working with dreams and evaluating the emotional and psychic energy, personal interpretations can be applied. For example, a house may represent the Self, and the quality of specific rooms can denote conditions within the psyche or allude to circumstances in waking life. For example, dreams including a kitchen can represent nurturing, or the absence thereof, and a bedroom can reveal aspects of a primary relationship. In terms of animal symbols, the book “Animal Totems” by Ted Andrews is particularly illuminating regarding the messages of animal visitations. Andrews details numerous historical interpretations from which to derive personal significance:

Reclaiming one’s true power: The panther (including all cats) is a symbol of ferocity and valor. It embodies aggressiveness and power, though without the [male] solar significance. In the case of the Black Panther, there is definitely a lunar significance. Of all the panthers, probably the Black Panther has the greatest mysticism associated with it. It is the symbol of the feminine, the dark mother, the dark of the moon. It is the symbol for the life and power of the night. It is a symbol of the feminine energies manifest upon the earth. It is often a symbol of darkness, death, and rebirth from out of it… (p. 294).

Symbolically, through the ages, the Sun has been infused with psychic projections of light, maleness, and logic, while the Moon has been imbued with projections of water, femininity, and emotions. The panther in the dream emerges from the right side (masculine/animus) as a silhouette; however, it is a feminine symbol. The duality of the panther archetype in this dream alludes to the interplay between the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious (Jung, 1969, p. 5). It is suggested that the theater of life is a continuous interplay between personal and collective unconscious.

Because the panther is an archetype, connection to it connects one to the larger whole. The dreamer is not alone at any point in this dream. The struggle is shared with significant others. This recognition allays feelings of suffering in isolation and moves the dreamer into the sphere of the collective unconscious, where suffering is universal to the human condition. With an understanding that elements of our complexes and resulting suffering are universally shared, moves one from a trauma-centered position and invites the development of compassion for oneself and for others.

The panther often signals a time of rebirth after a period of suffering and death on some level. This implies that an old issue may finally begin to be resolved, or even that old longstanding wounds will finally begin to heal, and with the healing will come a reclaiming of power that was lost at the time of wounding. Also, the Black Panther is very mystical, finding the most power in darkness. The Black Panther understands death and teaches people not to fear it, for out of death comes rebirth (Andrews, 1993, p. 294).

That two cubs merged into the larger “mother” cat signifies two-thirds of the dreamer’s life has already passed, and lessons have been integrated. This recognition bears significance to waking life. The arrival of the dark-mother jaguar signifies that by having meticulously confronted personal complexes, the dreamer may now assist others in transmuting their trauma into latent personal power. “Only the wounded physician heals” (Jung et al., 1976, p. 134). However, the fullness of the dream indicates that there is still a feminine element or remaining opportunity for balance present on the path of individuation. The theme of death and rebirth becomes more significant:

They make a left turn. But then, the dreamer sees a naked, dead woman on the left side of the road. She is dirty-blonde, Caucasian, lying face-down in the mud. The dreamer screams upon realizing that there is a dead woman on the side of the road. “Stop,” the dreamer screams, “I can’t believe it, but there is a dead woman on the side of the road. We have to call the police!” There is disagreement about whether to back up the van or stay put.

In the dream state, the dreamer was incredulous to encounter this scene. What old part of the self is ready to die off so that a more authentic aspect of Self can emerge? The conflict over whether to back up or stay put represents a potential sojourn into unfamiliar territory without the usual defenses, transferences, compensations, or persona mask. In this dream, the dreamer confronts archetypes of the feminine. The feminine archetype is reluctant to claim the driver’s seat. However, an activation has been presented, and with it the opportunity to confront biases and conditioning present within the shadow, such as what it means to embrace the feminine aspect, to be a fully present female, and to embrace the ferociousness of the feminine side, resurrect it, and integrate it at a manageable pace. “Archetypes are typical modes of apprehension. And wherever we meet with uniform and regularly recurring modes of apprehension we are dealing with an archetype, no matter whether its mythological character is recognized or not” (Jung et al., 1989, p. 57). Confronting archetypes infuses fresh possibilities into old complexes. New energy presents itself, and along with it, an opportunity to individuate—to become more of who one is—the authentic Self.

References

Andrews, T. (1993). Animal speak: The spiritual & magical powers of creatures great and small. Llewellyn Worldwide.

Jung, C. G., Aniela Jaffé, Winston, C., & Winston, R. (1989). Memories, dreams, reflections. Vintage Books, A Division Of Random House, Inc.

Jung, C. G., Campbell, J., & Hull, R. F. (1973). The portable Jung. Edited, with an introduction, by Joseph Campbell. Translated by R. F. C. Hull. (Fifth printing.).

Jung, C. G. (1969). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (H. S. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, & W. McGuire, Eds.; Second edition, Vols. 9, Part I). Bollingen Foundation.

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his symbols: Carl Gustav Jung: Free download, borrow, and streaming: Internet archive. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/B-001-004-443-ALL/mode/1up?view=theater

Kast, Verena. “Complex (Analytical Psychology)”; International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis, edited by

Alain de Mijolla, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2005, pp. 320-321. Gale eBooks, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3435300284/GVRL?u=carp39441&sid=bookmark GVRL&xid=3cc2a692. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

Sharp, D. (1991). Jung lexicon: A primer of terms & concepts. Inner City Books, 1991. Yontef, G. M. (1993). Awareness, dialogue & process: Essays on gestalt therapy. The Gestalt Journal Press.